2 min read

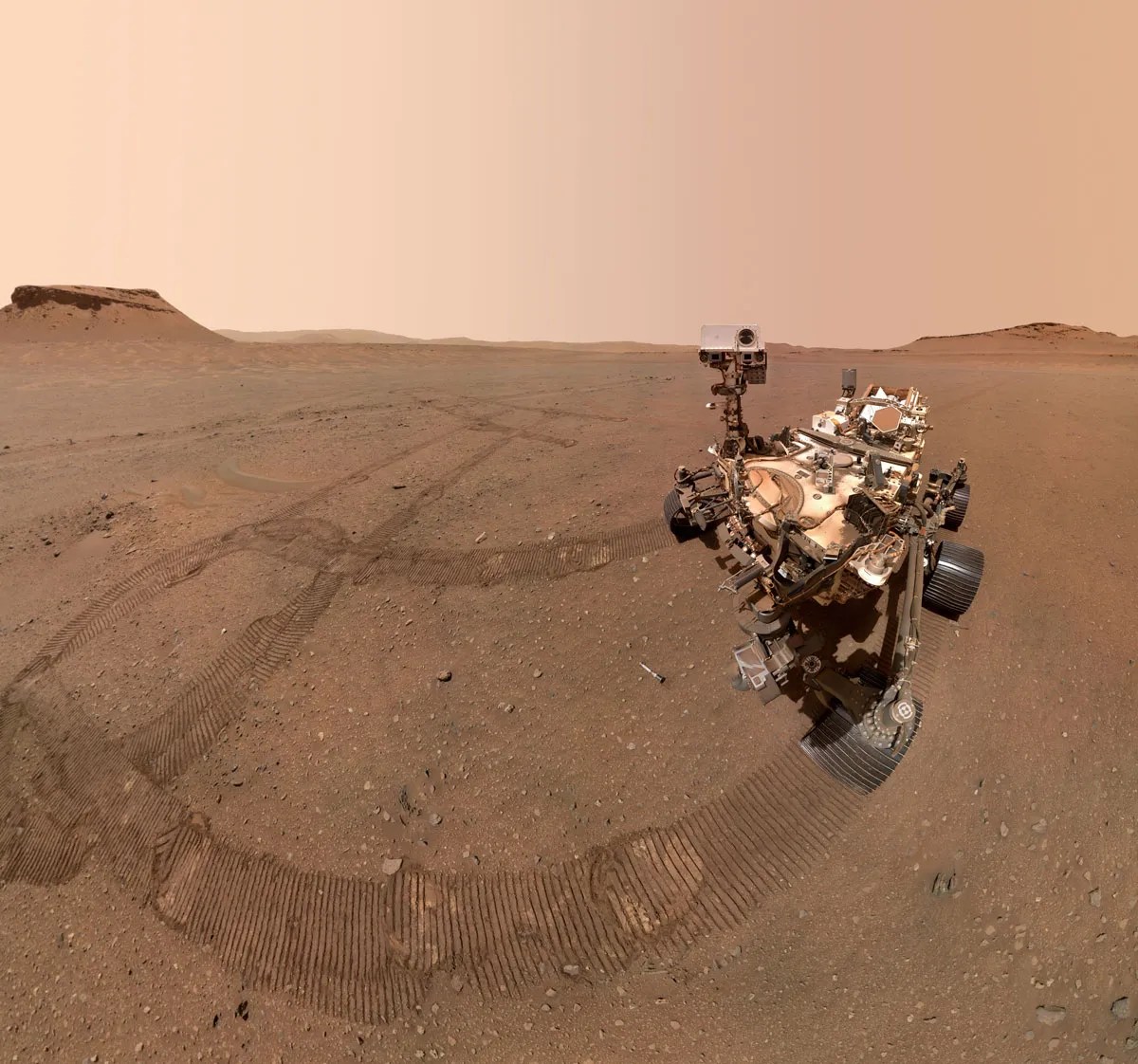

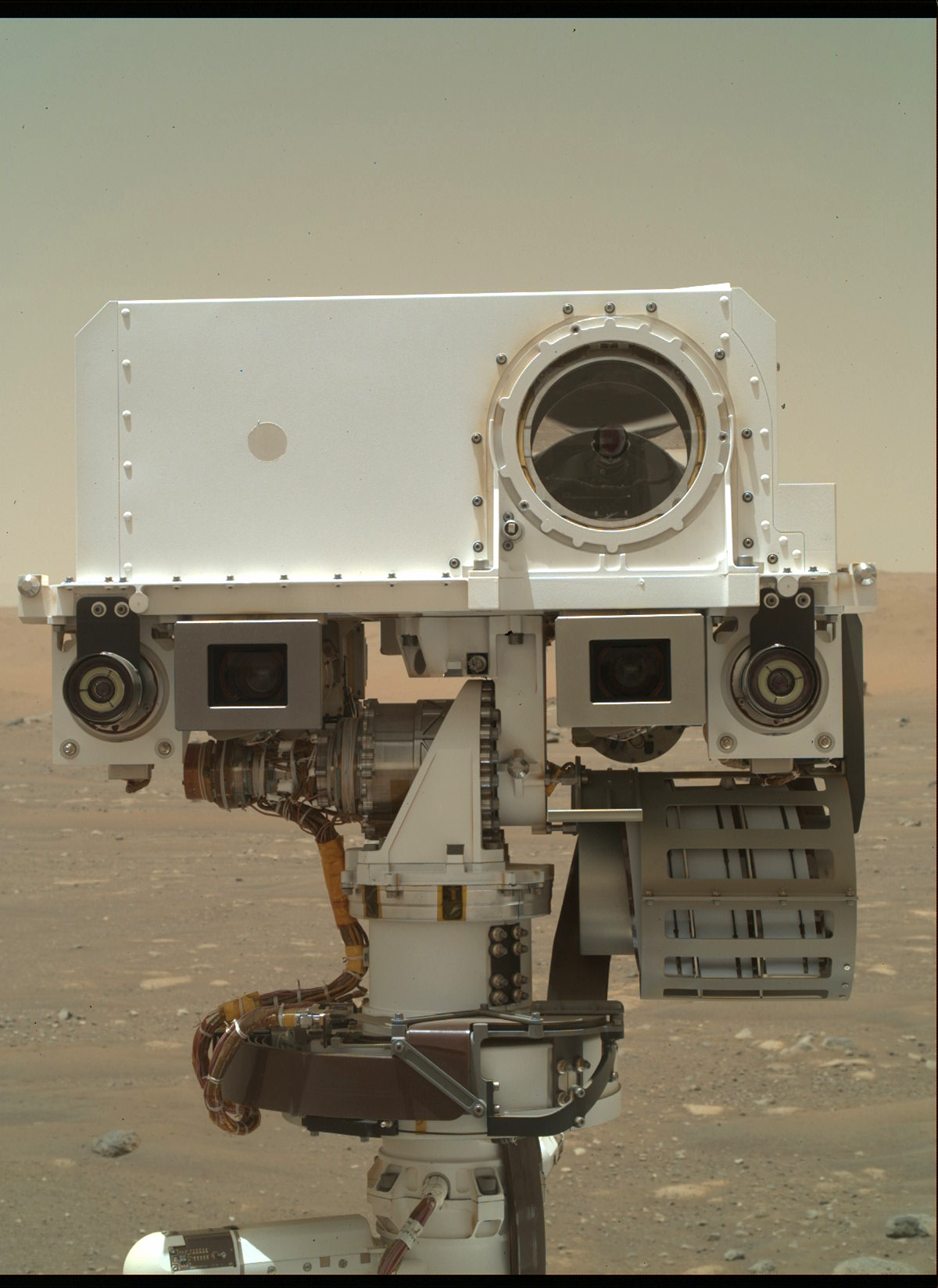

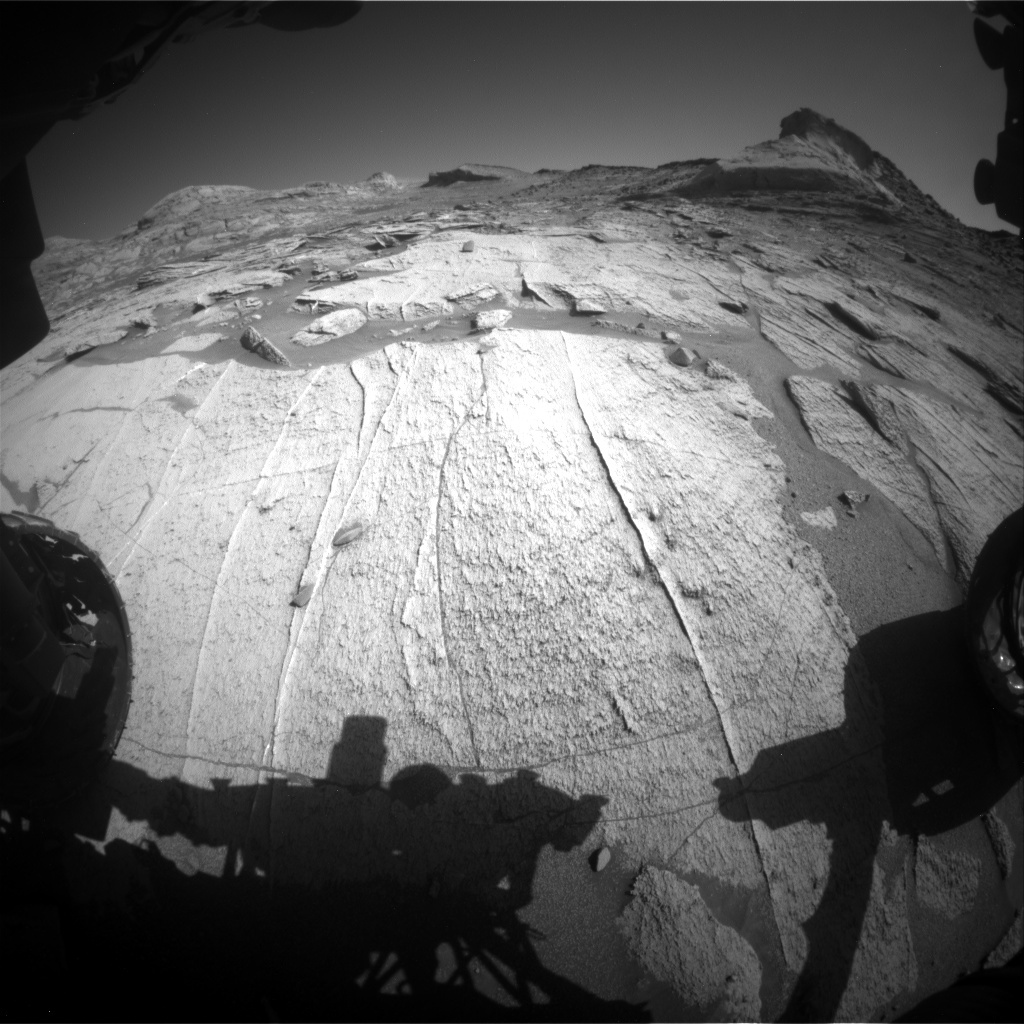

It’s another soliday weekend at Gale crater, which means we only planned two sols of activity today instead of the three we usually plan on weekends. Besides being a fun word to say, solidays are important because they help us realign our planning to match Earth and Mars’ constantly shifting time zone differences. Our two-sol plan today is relatively straightforward. We will brush the dust off of a vein running through the workspace we named “Joppa Salt,” and observe it with ChemCam, Mastcam, MAHLI, and APXS. We will also observe a second target, “Hope Park,” in our workspace with ChemCam, collect environmental science monitoring activities, and continue driving up Mt. Sharp.

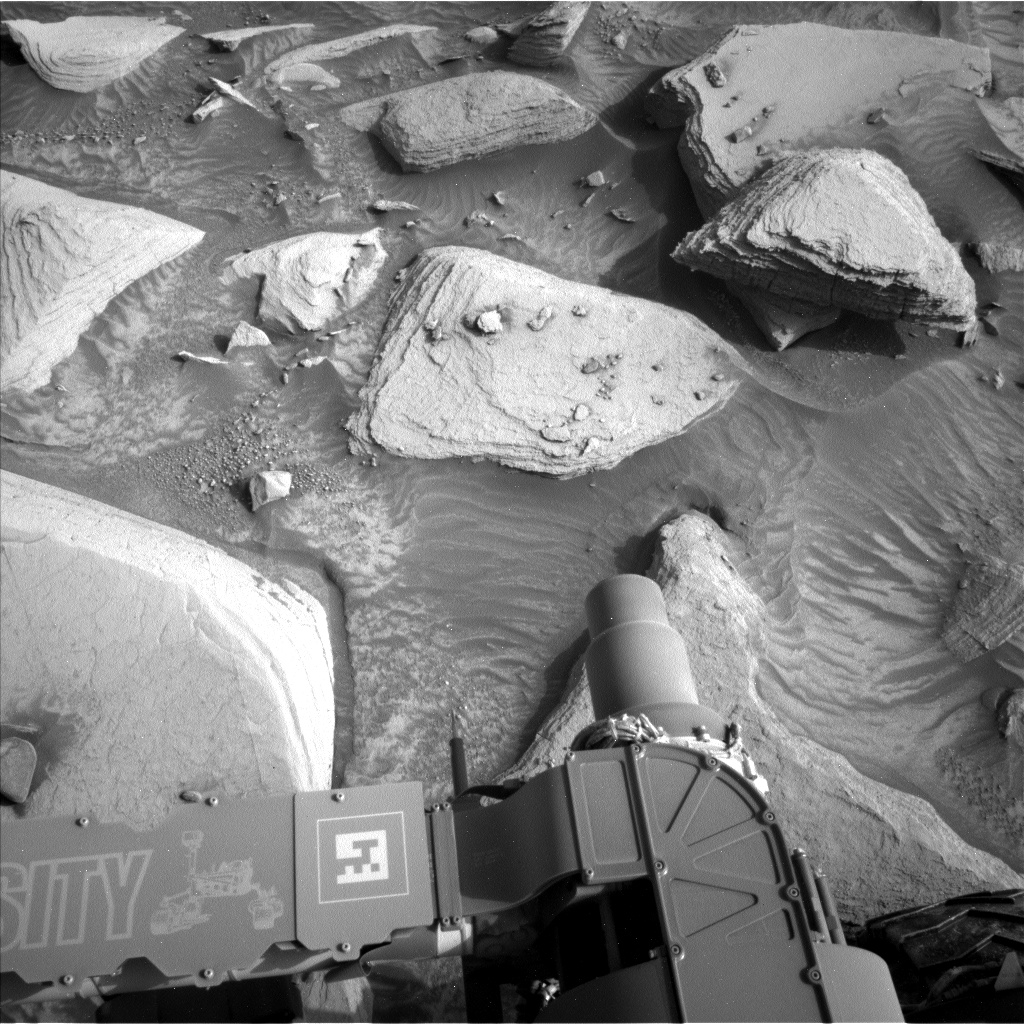

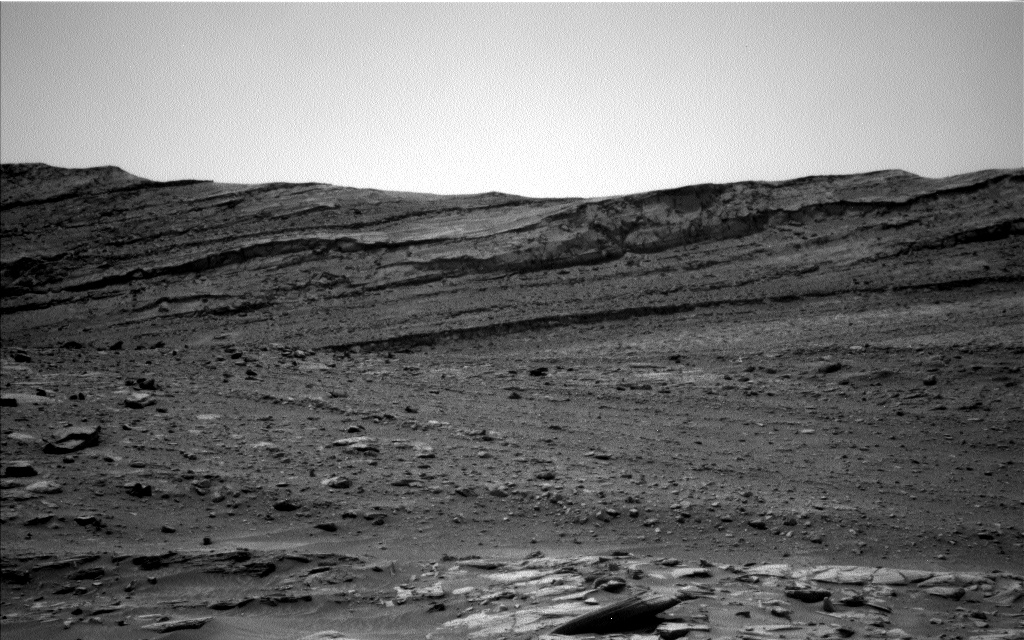

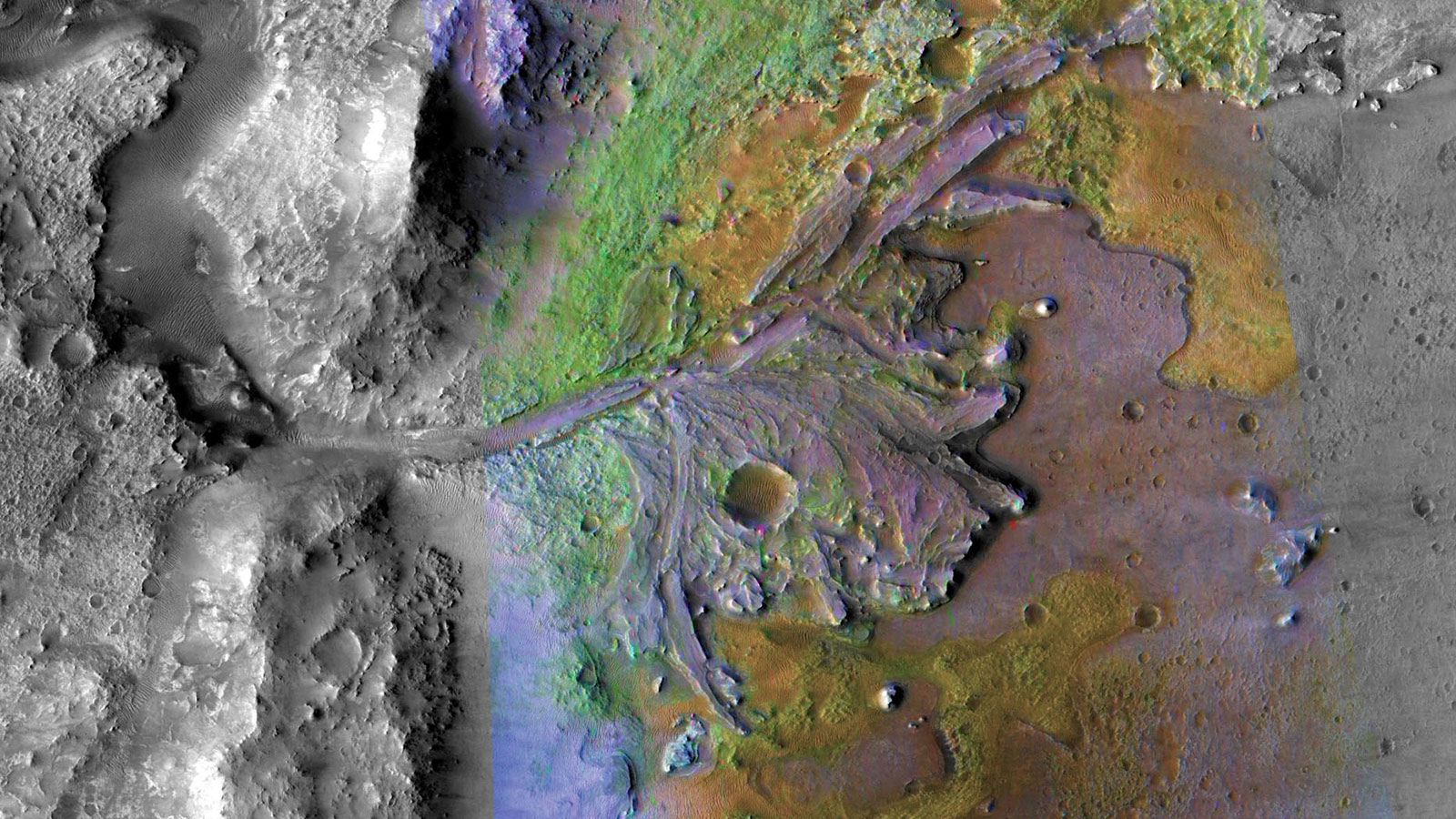

Our parking location today marks the closest approach to a feature we’ve named “Siccar Point,” so we’re also making sure to take lots of images of this feature. (Here was our view of Siccar Point a couple sols ago.) The dark rocks that sit on top of Siccar Point are much younger than the tan rocks below, and the contact between the two rock types marks a large break in time in the rock record. This kind of contact is referred to as an “unconformity” by geologists. Earth’s Siccar Point is found in Scotland, and it’s famous for historians of geology because of the spectacular unconformity exposed there. When James Hutton observed the unconformity in Earth’s Siccar Point in 1788, he realized it demonstrated the longevity of geologic time, and this notion led him to develop one of the key principles of modern geology: uniformitarianism. Uniformitarianism states that changes in the Earth’s crust throughout history have resulted from the action of continuous and uniform processes. I am excited to see what sort of new information we learn from Gale crater’s Siccar Point in the images we take this weekend.

Written by Abigail Fraeman, Planetary Geologist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory