After the commands for sol 164 were sent for the first sample acquisition and processing on the target Roubion, it was time to take some hours off and begin waiting for the result.

After the commands for sol 164 were sent for the first sample acquisition and processing on the target Roubion, it was time to take a few hours off and wait for the result. More than 90 engineers and scientists who had worked years preparing for this moment gathered online at 2 am PDT on Friday, August 6 to wait together for the first data from the coring operation. This data verified that the Corer had achieved the full commanded depth (7 centimeters) and we saw the image of the hole on Mars surrounded by the cuttings pile (material produced around the borehole during coring). So far, so good we thought as we signed off to try and get a few more hours of sleep before the next set of data arrived about 6 hours later.

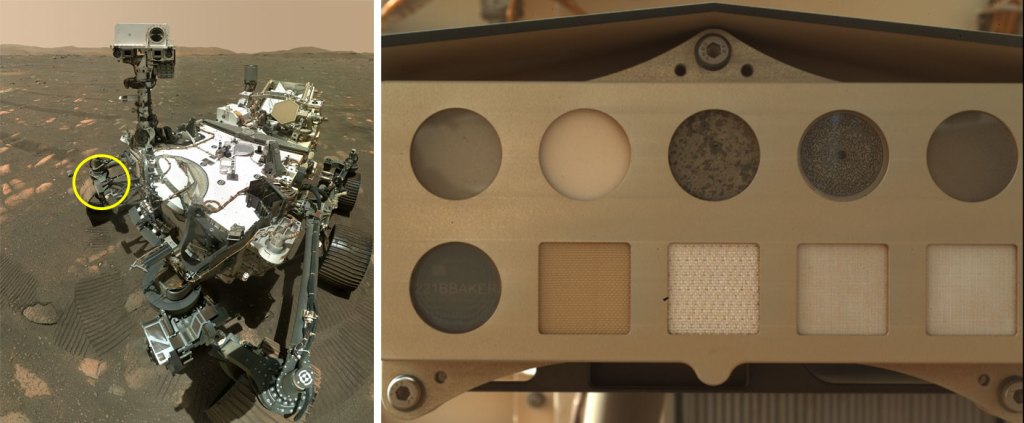

What followed later in the morning was a rollercoaster of emotions. Engineering telemetry and an image from the CacheCam inside the Adaptive Caching Assembly (ACA, the tube processing hardware) confirmed we had transferred the sample tube from the Corer to the ACA, sealed the sample tube, and successfully placed it in storage – a huge first-time success. The team was elated. Then the volume measurement and post-measurement image arrived indicating that the sample tube was empty. It took a few minutes for this reality to sink in but the team quickly transitioned to investigation mode. It is what we do. It is the basis of science and engineering.

What followed was two full days of combing through the data and adding more observations to the tactical plan to augment the investigation. Thus far we have concluded the following:

- Engineering telemetry of the Corer performance during both the abrasion and coring activities has not uncovered any unusual response compared to the data from our successful Earth-based testing (> 100 cores drilled in a range of test rocks);

- Imaging of the workspace in the areas over which the hardware has traveled during the post-coring activities has not resulted in finding an intact core or core pieces on the Martian surface;

- Depth measurements of the borehole derived from the merge of image products from WATSON along with the image itself lead us to believe that the coring activity in this unusual rock resulted only in powder/small fragments which were not retained due to their size and the lack of any significant chunk of a core. It appears that the rock was not robust enough to produce a core. Some material is visible in the bottom of the hole. The material from the desired core is likely either in the bottom of the hole, in the cuttings pile, or some combination of both. We are unable to distinguish further given the measurement uncertainties.

Both the science and engineering teams believe that the uniqueness of this rock and its material properties are the dominant contributor to the difficulty in extracting a core from it. Therefore, we will head to the next sampling location in South Seitah, the farthest point of this phase of our science campaign. Based on rover and helicopter imaging to date, we will likely encounter sedimentary rocks there that we anticipate will align better with our Earth-based test experience.

The hardware performed as commanded but the rock did not cooperate this time. It reminds me yet again of the nature of exploration. A specific result is never guaranteed no matter how much you prepare. Despite this result, science and engineering have progressed. We achieved the first complete autonomous sequence of our sampling system on Mars within the time constraints of a single Sol. This bodes well for the pace of our remaining science campaign. We are looking forward to the next sampling attempt in South Seitah, anticipated in early September.

Written by Louise Jandura, Chief Engineer for Sampling & Caching at NASA/JPL