4 min read

If your name begins with “L” you will like this post about the first letter to be laser engraved on Mars. Every once in a while, we see cartoons in which a Mars rover is driven in a pattern to make letters in the sand with its wheel tracks. The letters spell out a silly phrase, and the cartoon usually has aliens on the side, laughing or puzzling over the meaning. The use of lasers on board Mars rovers has also made it possible to laser-mark graffiti on Martian rocks. As NASA’s instruments are generally used strictly for science, I did not believe laser graffiti would ever be done. But of course, people have thought about it. When I arrived at JPL for the landing of Curiosity in 2012, I was surprised to find that one of our engineers in charge of developing sequences for SuperCam’s predecessor had written a lengthy sequence that would use the laser to spell out the instrument’s name on the rock surface. It was all in fun--we never wasted our shots using that sequence. However, on Perseverance, we have found a reason to use laser marking.

About two years ago I received a call from Professor Ben Weiss of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology asking about SuperCam’s laser marking capabilities. Ben had had just joined Perseverance as part of the Return Sample Science team, a group focusing on the collection of samples for return to Earth, with the purpose of ensuring that samples would be collected under the appropriate conditions to optimize their scientific value once back on Earth. Ben’s specialty is paleomagnetism. In terrestrial rocks, this is the study of the magnetism induced by the Earth’s magnetic field at the time of the rock’s formation. Mars currently has a very weak magnetic field, but Mars’ field strength in the past is largely unknown. It has important implications for the retention or loss of Mars’ atmosphere over time, among other things. Suffice it to say that we would love to use the samples returned from the Perseverance mission to fill in that knowledge gap.

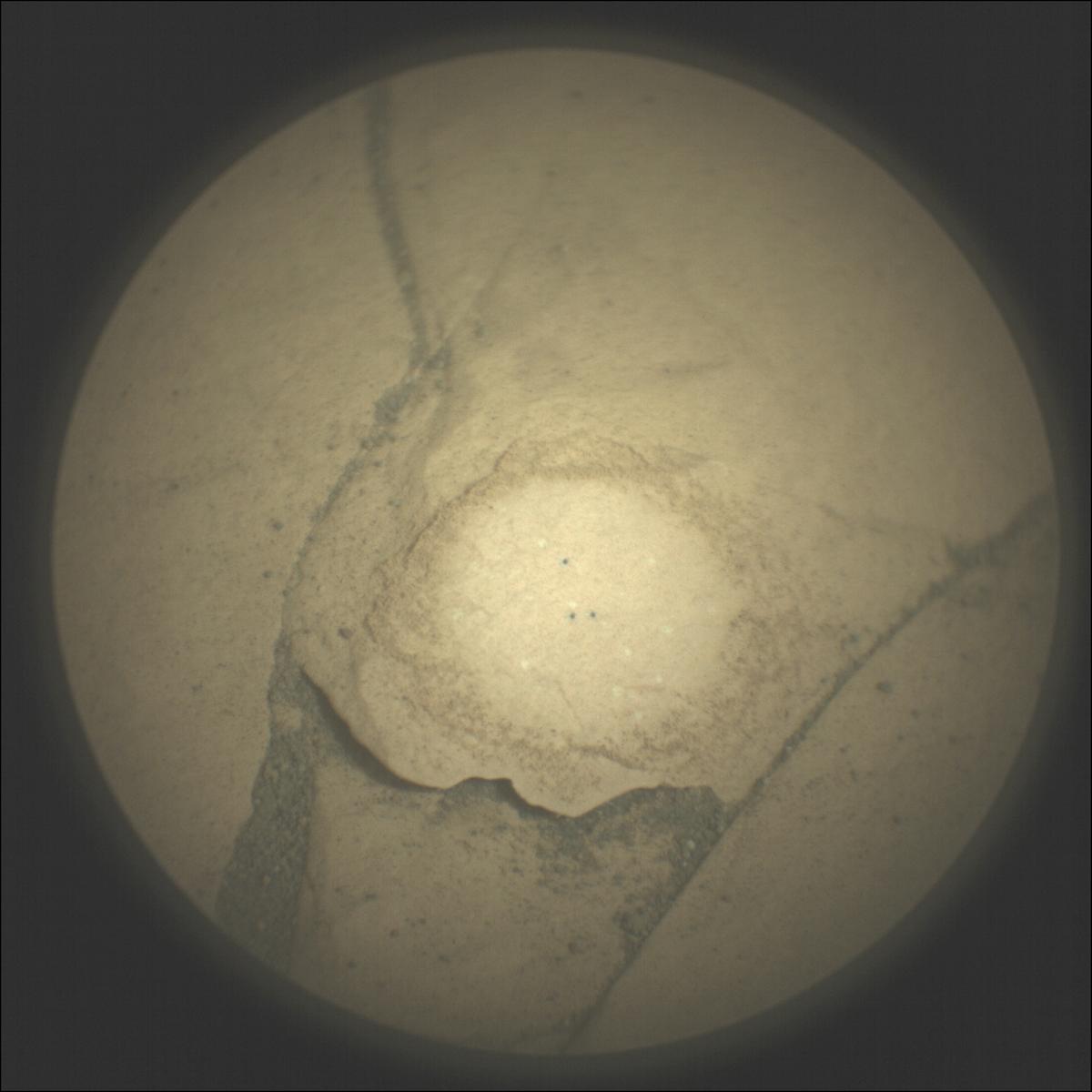

To do that, for each Mars rock core sample that is returned, we need to know its original orientation. If the surfaces of those core samples have easily recognizable features, that’s no problem. That has been the case with the cores collected so far. However, if the surface is fine-grained, there may be nothing to distinguish its rotational orientation. In that case, we need to make artificial markings on the surface.

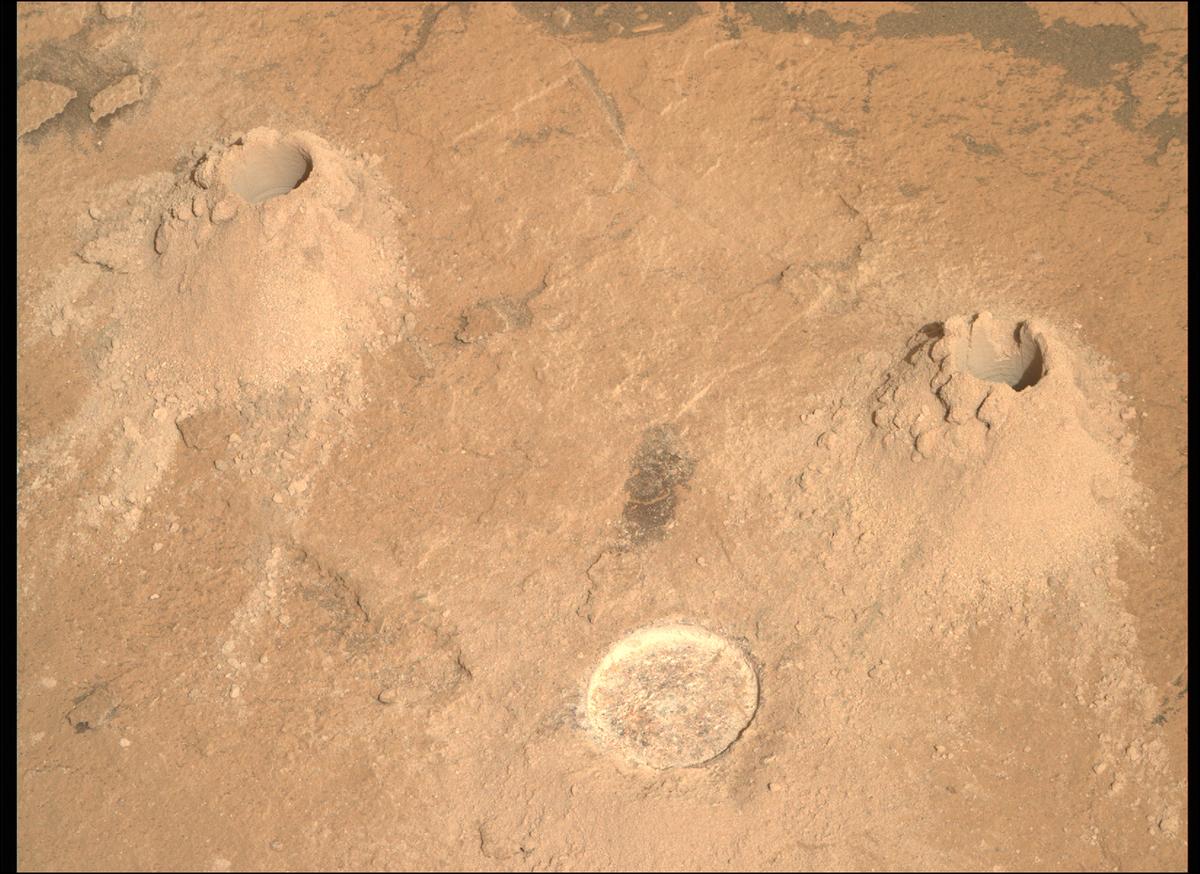

We don’t have a dark marker pen, but we do have a pulsed laser. So Ben’s call to my lab a couple of years ago got us thinking how to mark the sample cores, and we started some tests. JPL shipped several rocks of varying hardness to Los Alamos National Laboratory where they were marked with pits made with different numbers of laser shots. The rocks were sent back to JPL for subsequent coring.

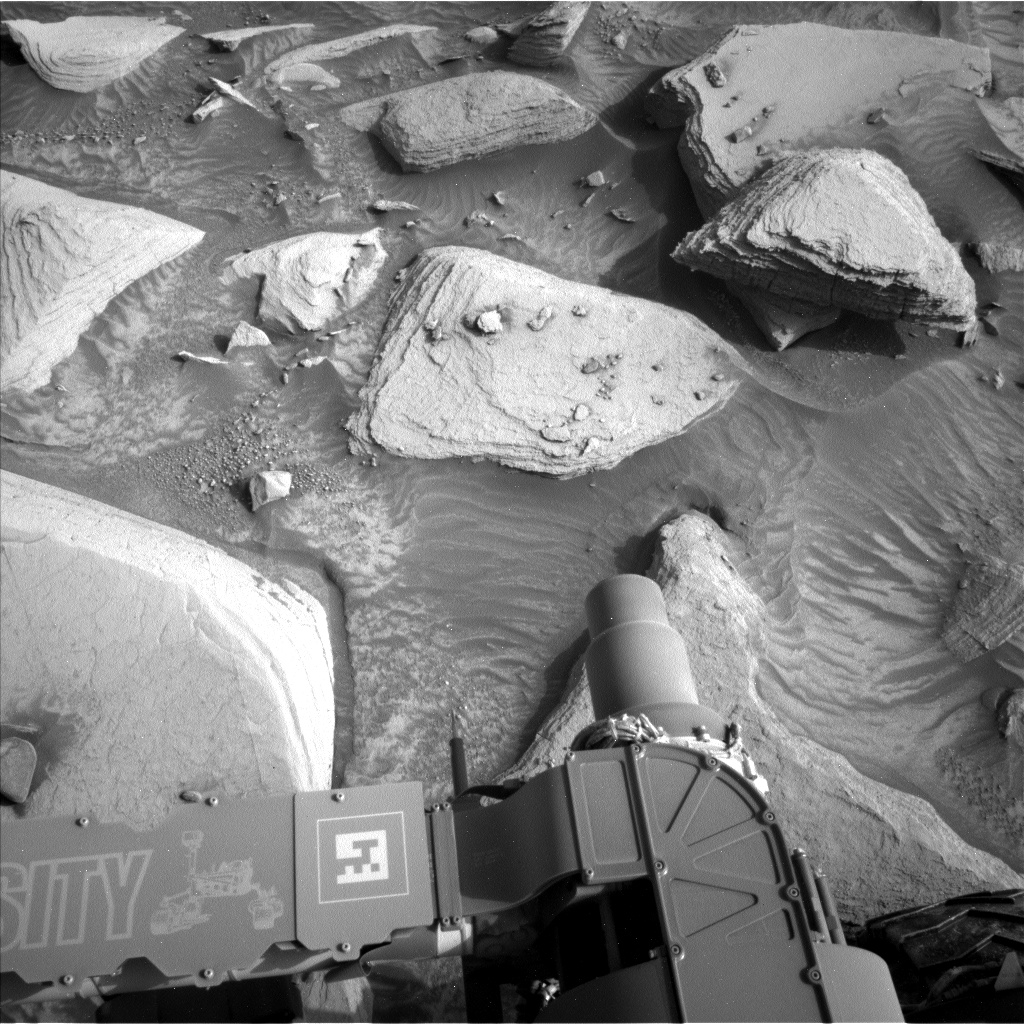

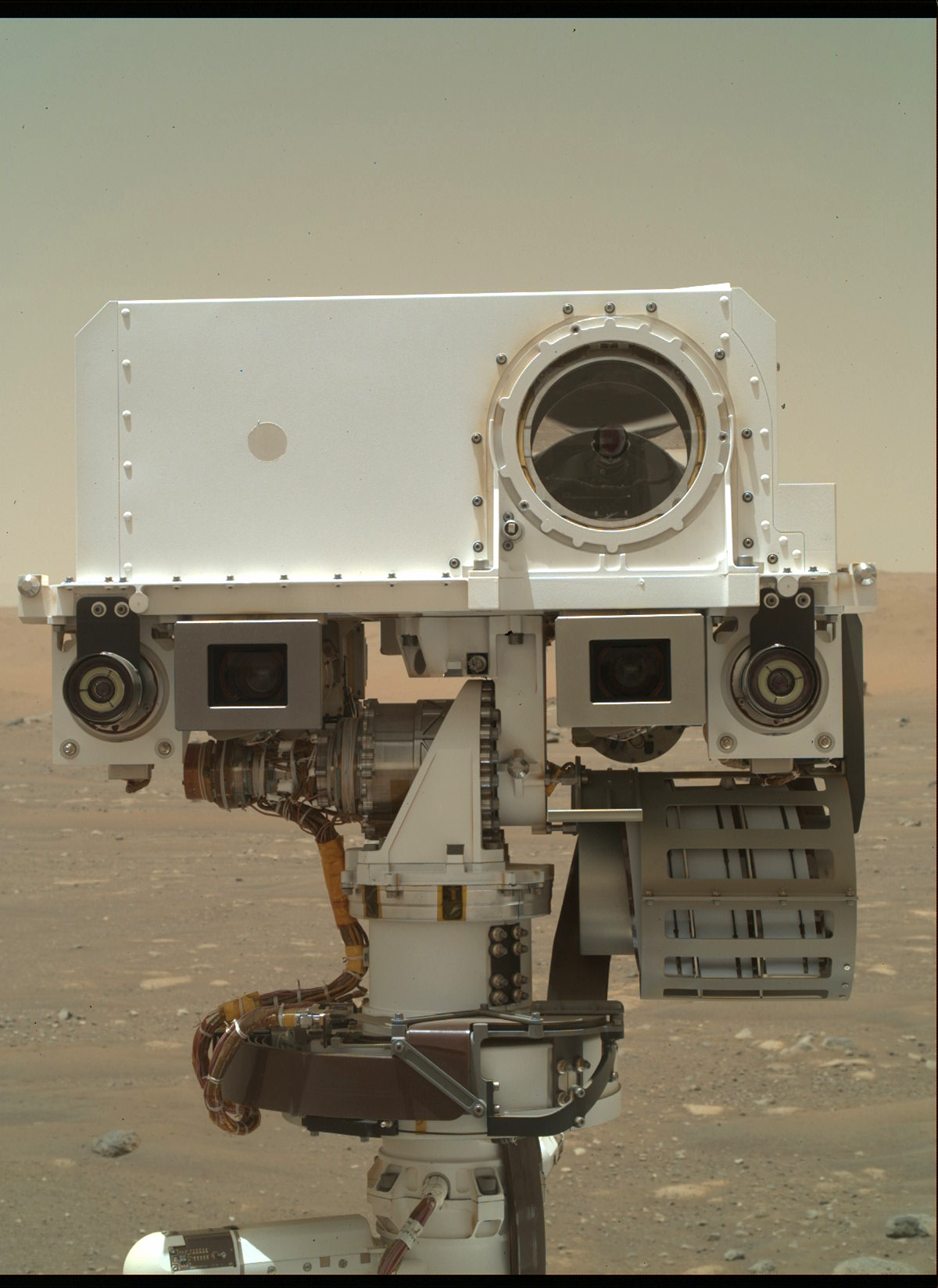

Fast forward to summer 2022. The SuperCam team was asked to be ready to mark a rock for coring with just a few days of notice. I was on SuperCam operations, and seeing how soon we might need the marks, we decided to switch from a normal observation to a core-marking sequence as a dry run. We had prepared various patterns for the mark. The basic principle is to understand the rotational orientation of the core after it has been removed from the rock and placed in the sample tube. For that, any asymmetrical pattern such as an arrow, would do. However, wanting to be efficient, we decided to use the simplest such pattern, consisting of three points (or laser pits) with unequal distance between them, like a capital letter “L.” SuperCam normally performs line scans (a single row) or grid patterns. To produce the “L” shape, we took a 2x2 grid pattern and removed one point from the sequence, so the laser only made three pits. Using 125 laser shots per pit, the result is shown in the image of the “Pinefield Gap” target. Sample cores are 13 mm (0.5”) in diameter, so the L patterns should fit well on their top surfaces. With the dry run successful, we are ready to use the procedure to mark future samples.

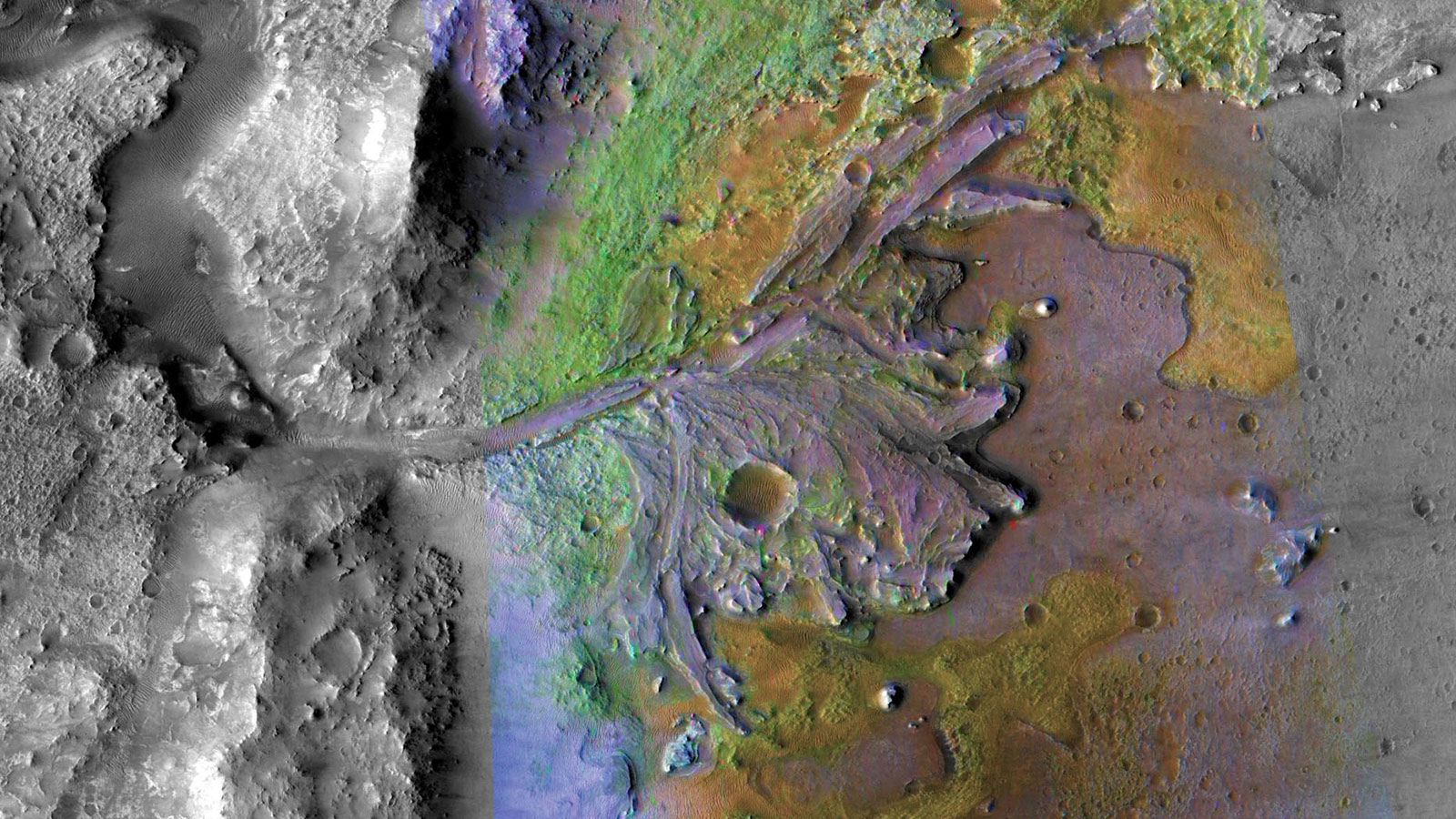

Over the last week, Perseverance completed its second of two samples from Jezero crater’s delta formation, from the Skinner Ridge block at Hogwallow Flats. Over the weekend Perseverance drove about 25 meters to Wildcat Ridge, located slightly lower in Hogwallow, for more exploration.

Written by Roger Wiens, Principal Investigator, SuperCam / Co-Investigator, SHERLOC instrument at Purdue University