Mars Exploration Rovers: Spirit and Opportunity

NASA’s Spirit and Opportunity rovers were identical twin robots that helped rewrite our understanding of the early history of Mars.

Mission Type

Objective

Destination

LandingS

Meet Spirit and Opportunity

Mars Exploration Rovers In Depth

-

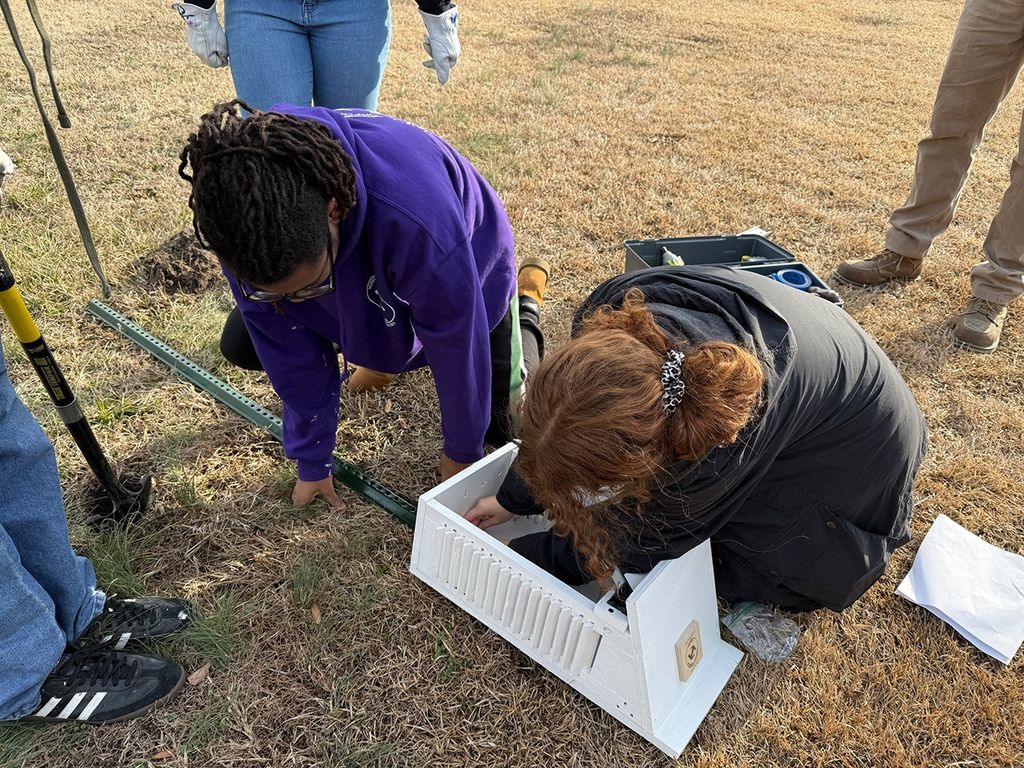

Rover Basics

Each robotic explorer sent to the Red Planet has its own unique capabilities driven by science. Many attributes of a rover take on human-like features, such as “heads,” and “bodies.”

-

Objectives

New knowledge from the twin rovers uniquely contributed to meeting the four overarching goals of the Mars Exploration Program, while complementing data gathered through other Mars missions.

-

Science

By studying the rock record, Spirit and Opportunity confirmed that water was long standing on the surface of Mars in ancient times.

-

Landing Sites

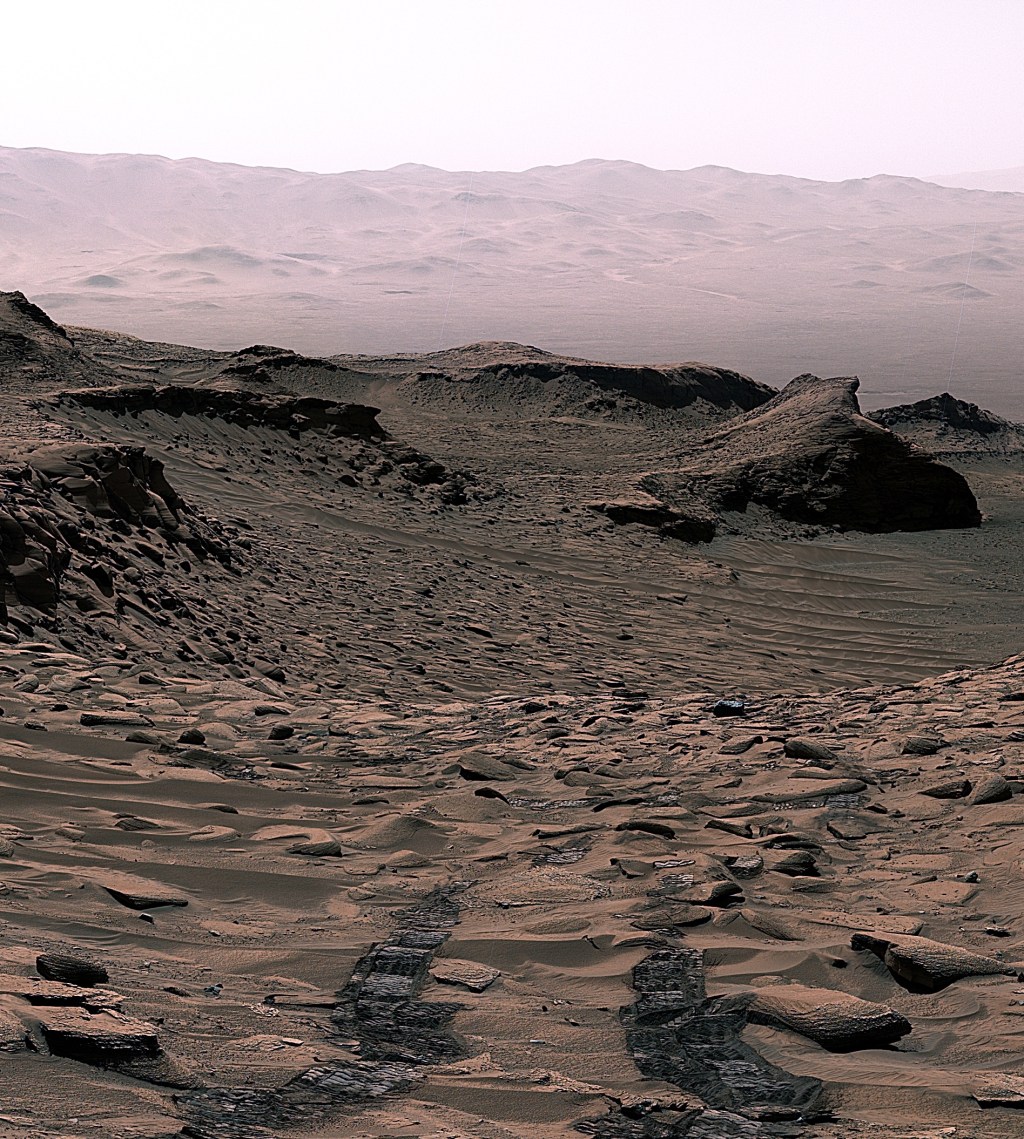

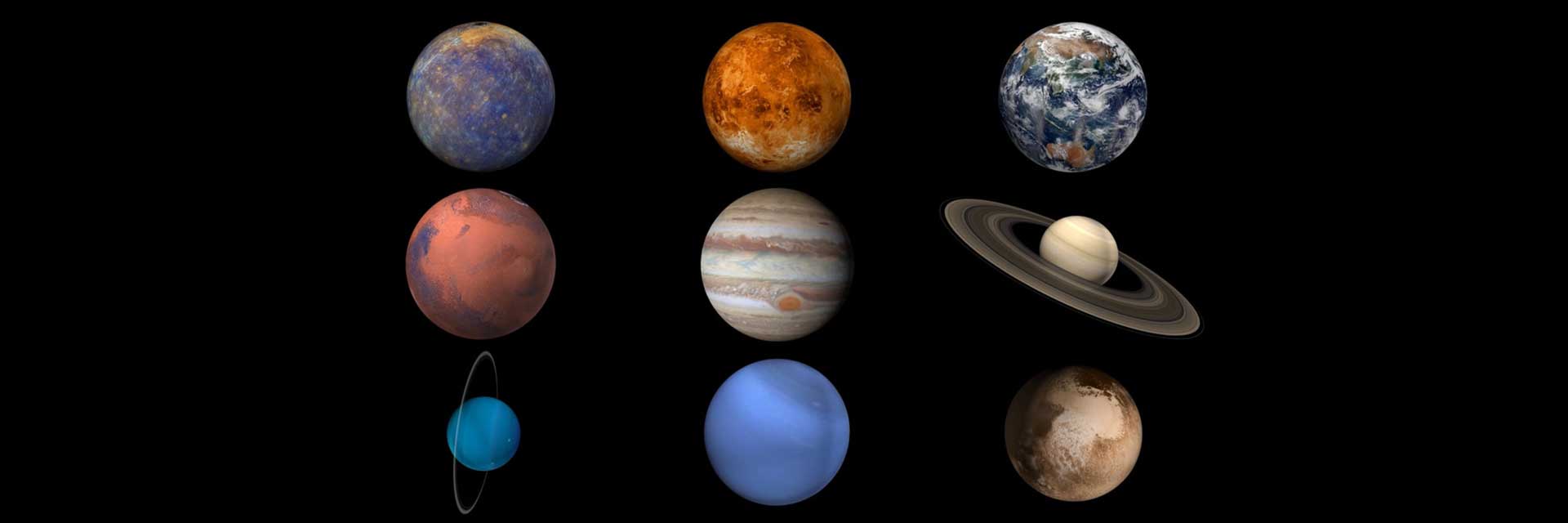

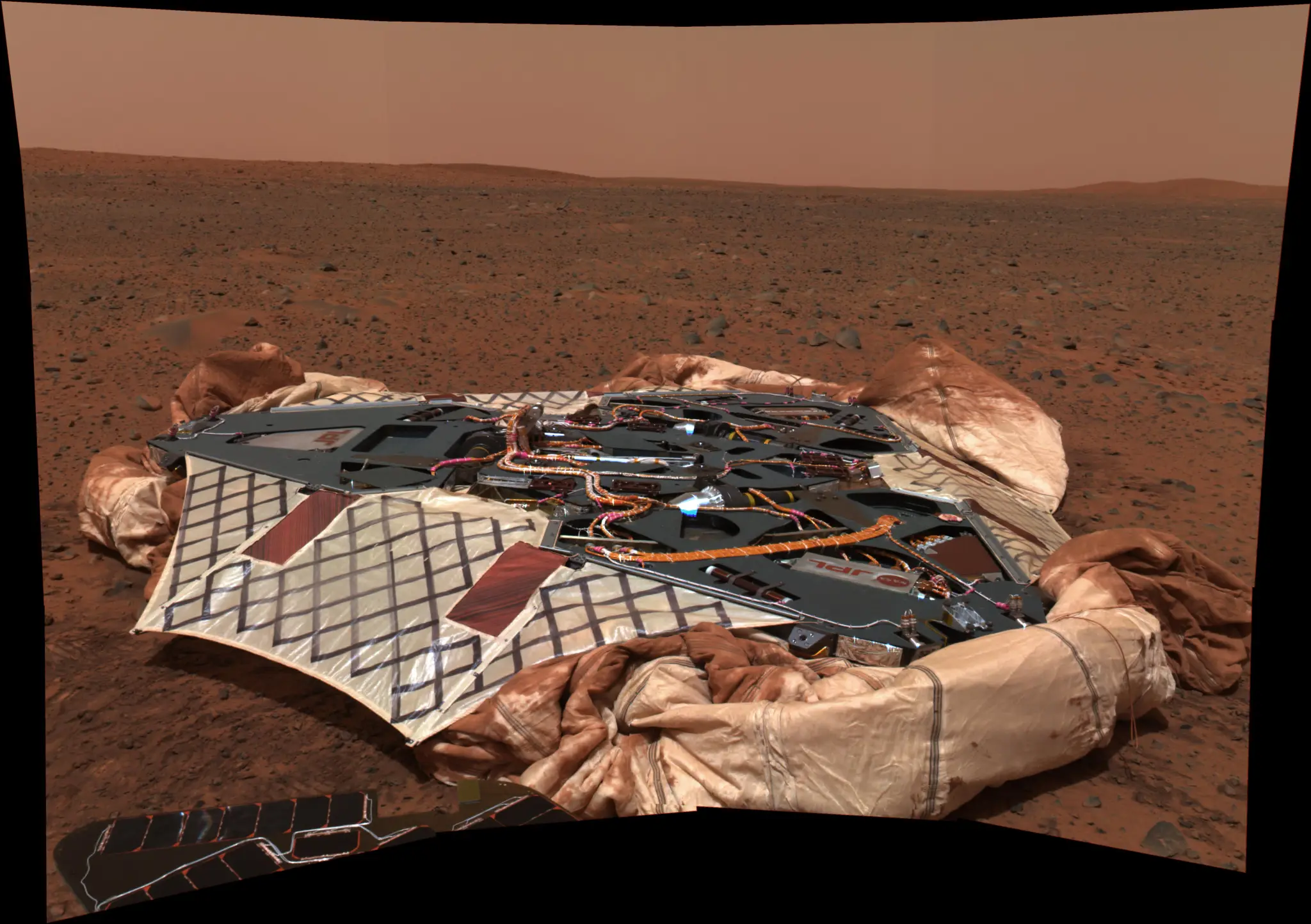

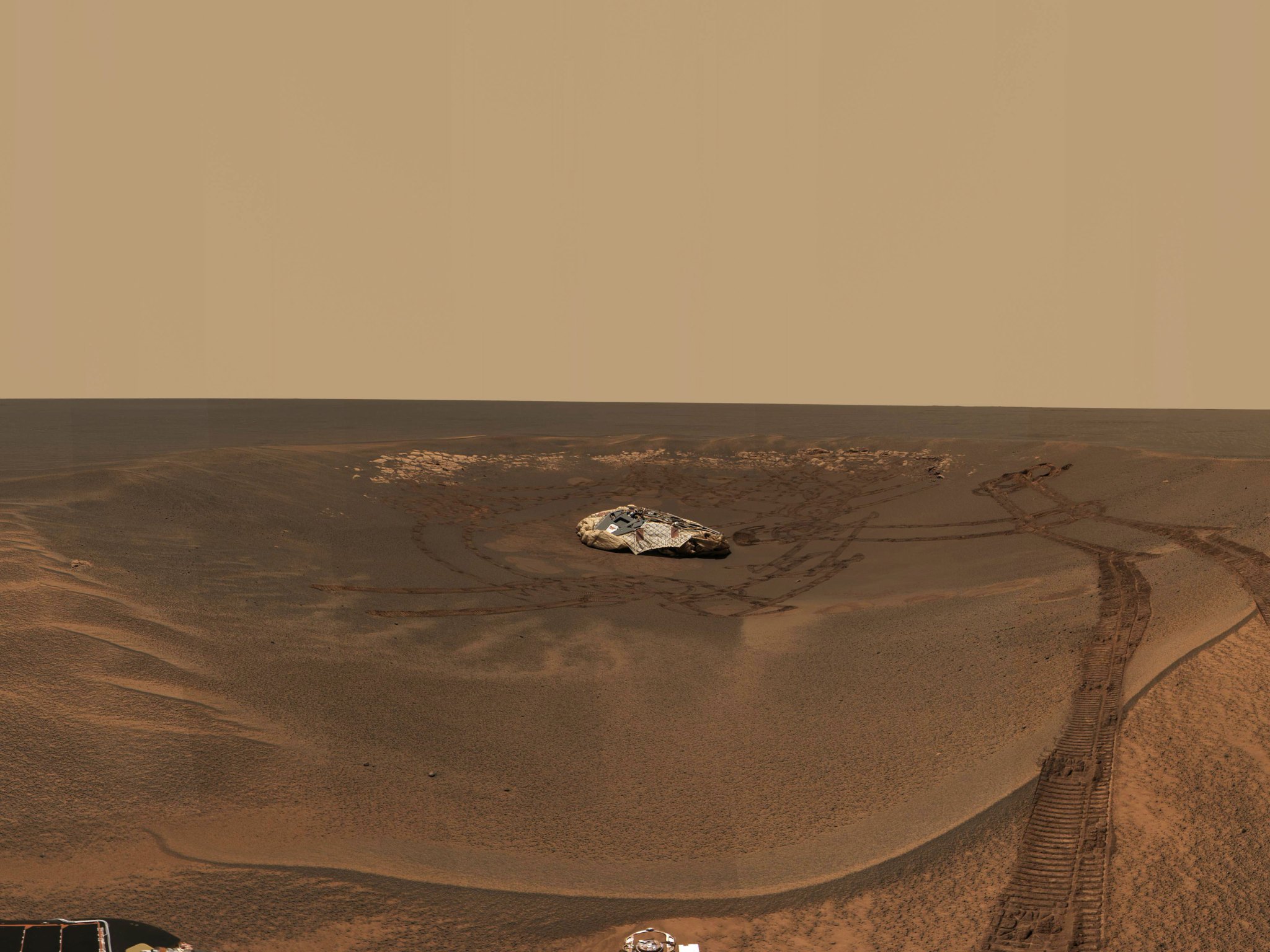

The rovers were targeted to land at sites on opposite sides of Mars that looked as though they were affected by liquid water in the past. Spirit landed at Gusev Crater, a possible former lake in a giant impact crater. Opportunity landed at Meridiani Planum, a place where mineral deposits suggested that Mars had a wet history.

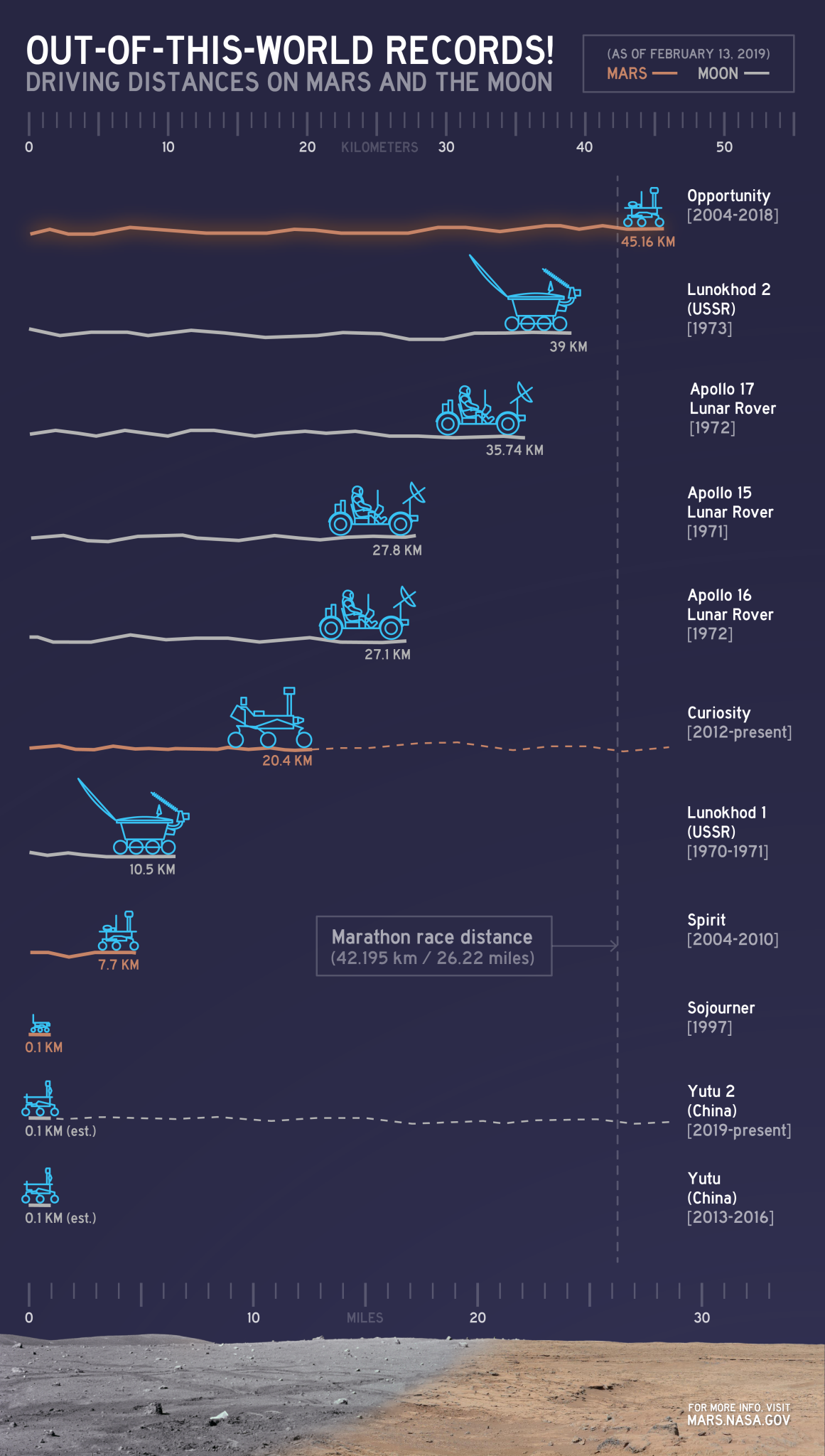

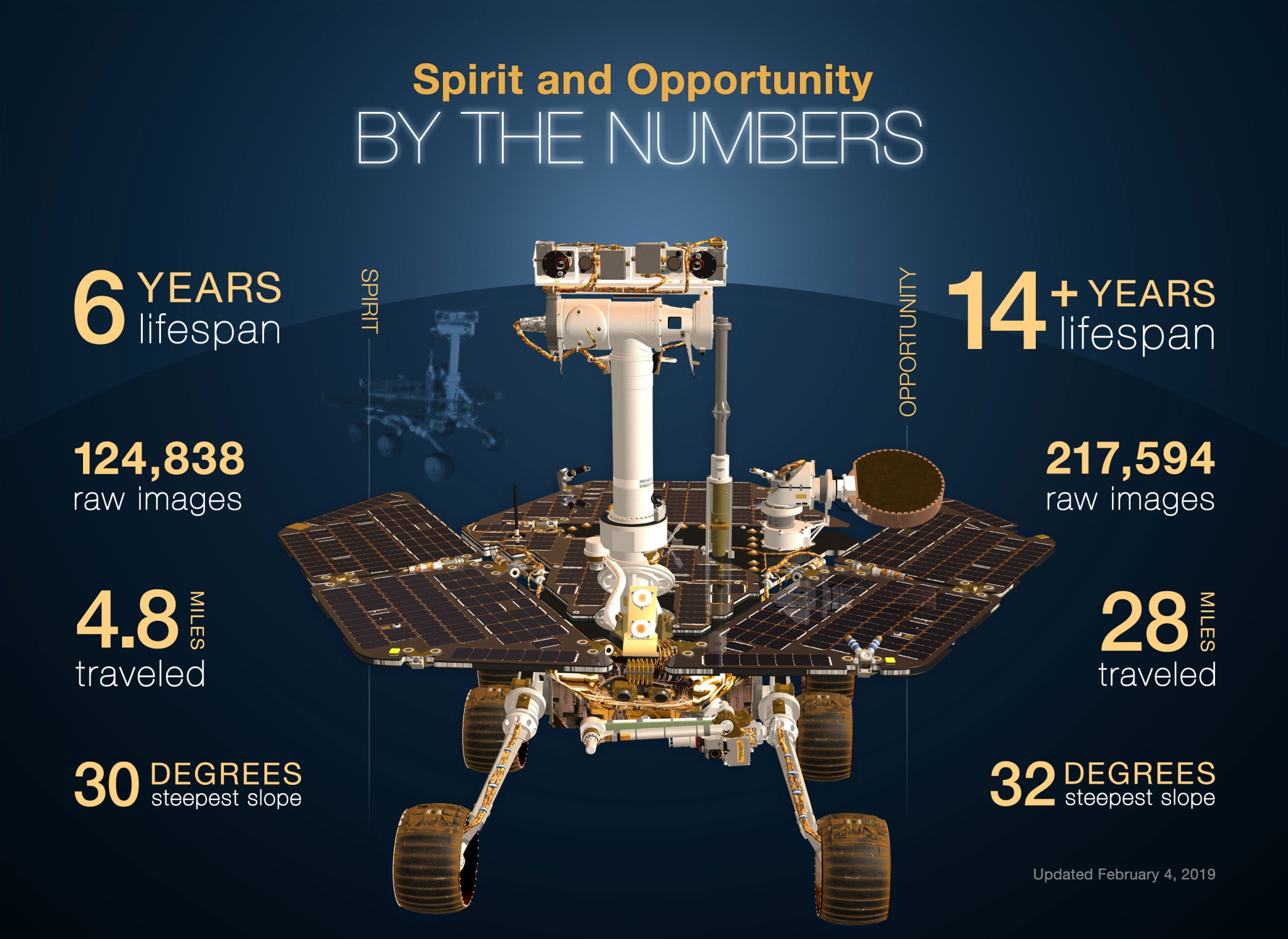

Going the Distance

By the end of its mission, Spirit journeyed 4.8 miles (7.7 kilometers) on Mars. Opportunity holds the off-Earth roving distance record after accruing 28.06 miles (45.16 kilometers) of driving on Mars.