3 min read

On sol 3415 we encountered what we unofficially dubbed ‘Gator Back’ terrain and decided to not fight the “creature” on the expense of our wheels but rather to turn around and go back. For those of you who like looking back into the events: the first encounter with that terrain that made us turn around was reported here on the blog on sols 3419-3420, blog 3421 showed a beautiful close up of the “beast,” and we decided to turn around on sol 3422. All this was not only reported in the blog, but also in a Curiosity news piece that has a beautiful panorama view of the gator back.

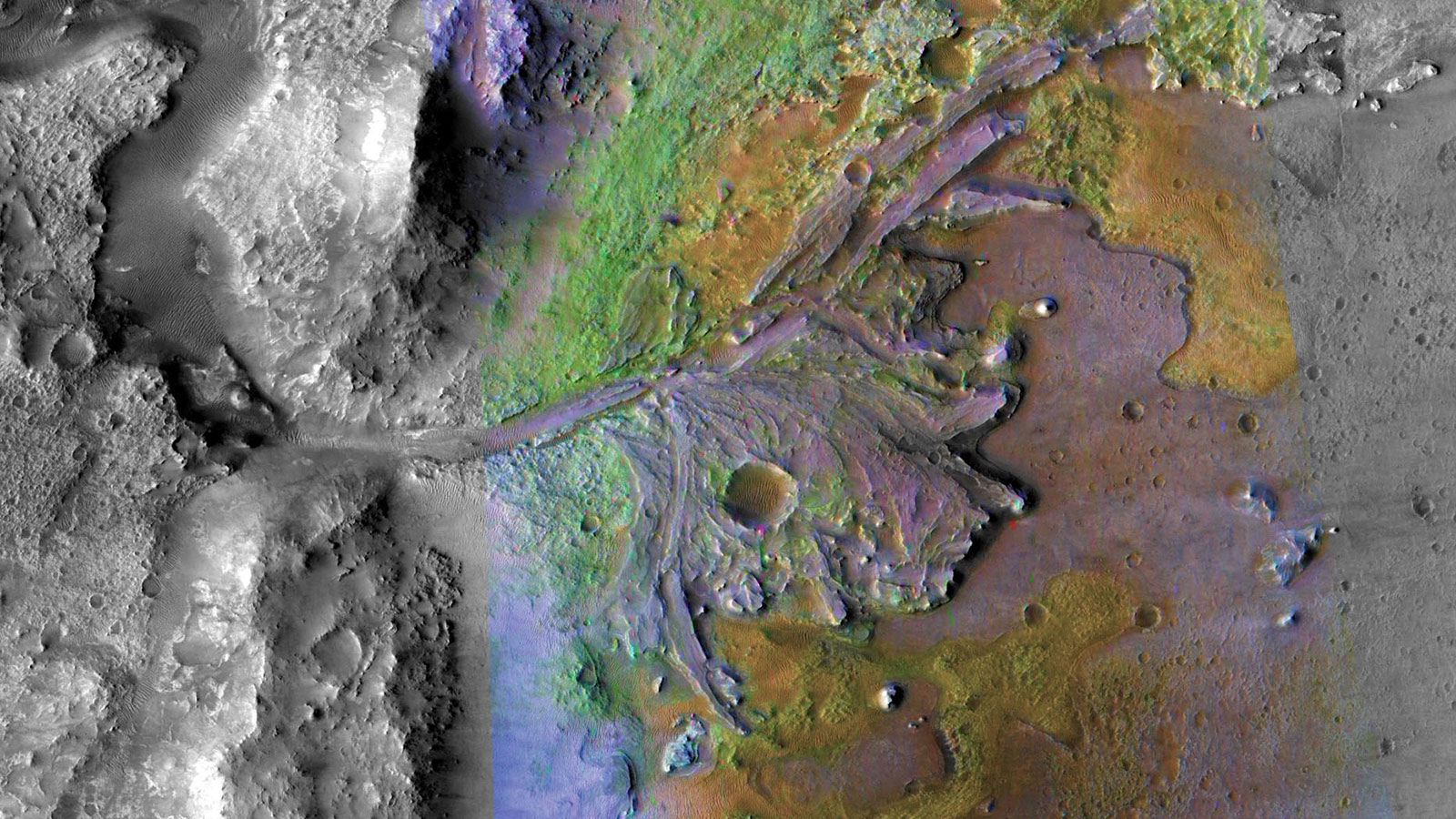

The fact that we turned around, something that very, very rarely happened in the rover’s 3463 sol history, is now very important for a science question: how much does Mars change? You may know that we regularly do change detection imagery when we are stationary for a drill campaign. We repeatedly take images of the exact same sand patch in the rover’s vicinity, which allows us to observe grain movements over a few days or weeks, and using those assess the wind activity at this place. Tracing back our steps from the pediment, we now have the very, very rare opportunity to do a similar experiment but with a much longer duration: imaging our wheel tracks from the ascent, which are by and large 100 sols old by now, we can assess how those tracks have changed over time and therefore the erosional activities acting on those tracks.

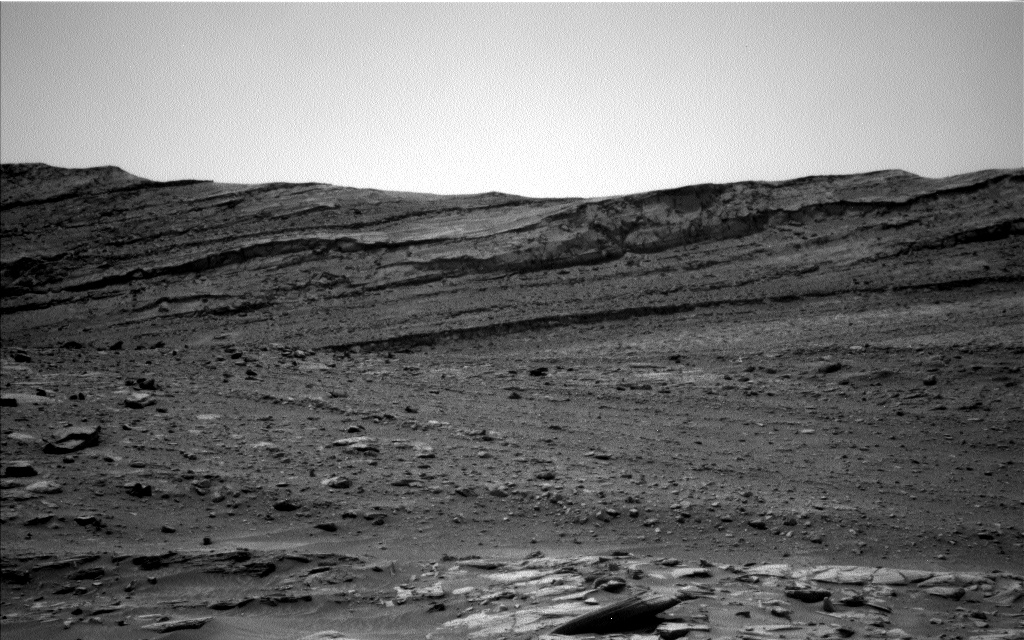

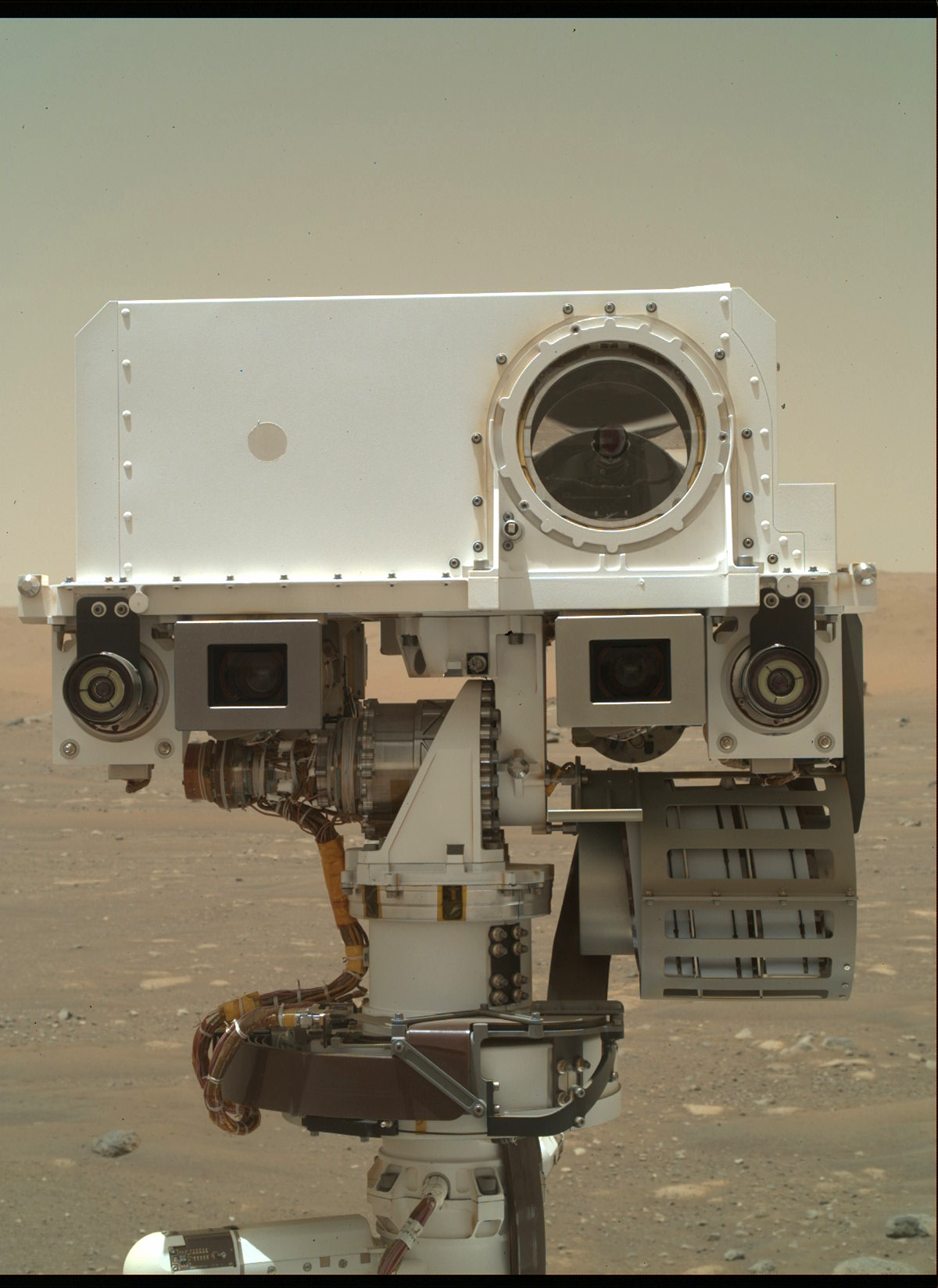

Sounds easy? Well, the first question was if the tracks in front of us – you see one in the image above – for sure are old tracks. This question sparked a brilliant example of engineering and science working together (and why this blogger loves working with this team so much!). Our science planning group was not quite sure of the age of the tracks, so we explained to the engineers what it was that we wanted to achieve. The engineers dug though all their data to make sure we indeed have old tracks in our view. Once the engineers confirmed that we had 100 days old tracks in front of us, Mastcam planned three observations on different parts of those tracks. In addition, there is a Mastcam observation on bedrock, which is also a ChemCam LIBS target called ‘Caracarai.’

We also have atmospheric observations in the plan and a long drive to get us into a good location for science tomorrow. If you now wonder why there is no APXS and why MAHLI did not join the image-the-old-tracks feast, then that’s courtesy to Mars, who decided to put a rock right under our front wheel. With Curiosity perched on a rock, we played it safe, as always, and left the arm stowed. Hopefully, APXS and MAHLI get to join the measurements tomorrow again.

Written by Susanne Schwenzer, Planetary Geologist at The Open University